I’m headed to Bucaramanga, Colombia to get certified to paraglide. I planned this trip, oh, six days in advance. I have no experience, just a love for the sky and freedom and the g-forces I felt on a tandem flight years ago. The first step is getting to Bogota, Colombia. I arrive at 2am, alone. My eyes blur the huddle of caffeinated drivers shouting taxi señora? and the long yellow streak at the curb. I shake my head no and explain that I’m waiting for friends. But I’m not.

I already have my bags, a small backpack and a mini carry-on. I’ve just changed dollars into pesos– each dollar for some 2,800 pesos. How do people buy houses or cars that must cost billions with all those zeros? I scope out some Americans huddled around the baggage carousel (turns out they’re Danish) and we share a cab through Bogota’s wet streets. We’re headed to different hostels in La Candeleria, the old cobbled neighborhood that butts up to guardian green mountains. We talk traveler in a 3am haze- are you gonna do the Lost City Trekk? The Salt Mine? They have the 5 pound Lonely Planet guide, and each other. When I shut the door on my brief comrades, I’m alone again in the drizzle ringing the buzzer of a small wooden door.

I have less than 24 hours before my flight to Bucaramanga. Enough to grace the edge of the city, eat fried ants for breakfast with a young Mexican couple, and walk past graffiti and memorials of assassinated heroes.

I board a smaller plane this time, one blonde head in a forest of brown and black. Forehead to the plexiglass over Chicamocha Canyon, clouds reflecting in the twisting brown river. I ask my seat mate about the smoke trails climbing out of the matted jungle mountains, and he just shakes his head. Maybe my Spanish is abysmal, I’m not sure. At the tiny airport, I ask the closet-sized Information booth to help me get a better address for Colombia Paragliding. I have a notebook where I wrote, “2 kilometers via Ruitoque, Floridablanca.” Even considering that this is my first time in South America, it doesn’t look like an address to me. The girls in the booth click nails, speed-talk Colombian into curly phones, and confirm that there is no precise address. “Dice p a r a p e n t e,” they tell me in slo mow, giggling. Paraglide.

Outside at the curb there’s a beat up plastic cup batting between the sidewalk and a concrete wall in the wind. I look at a dog slumped there, itching. I snatch up the cup and pour the last of my water into into it, sliding it under the dog’s silver haired nose. A taxi driver leaning against his car laughs and yells lo vive aca! He lives here! Flies buzz around the black and white mutt. He ignores the water and keeps itching.

Well the fourth taxi driver I ask has at least heard of the parapente place on Ruitoque Road. Thank god I arrive before nightfall, when you can’t see the signs painted on concrete. Some people ring our buzzer in the middle of the night with a police escort, my instructor Russell explains one day. The cops are always around, he says, so when the taxi drivers don’t know what to do with people, they step in.

DAY ONE

“Uhh. We need that heavier harness.”

I’m standing on the scale with all my gear, waiting to hear the verdict.

The other instructor German chimes in, “more hamburgers and cervezas for you girl!”

The glider I’m going to use is meant for 65-75 kilos, and I’m pushing 61. For the first time in Colombia Paragliding’s history, all the paragliding students are girls. Skinny girls. It’s like going into a clothing store and the Tween Team just blew through and bought out everything cute in size Small. So I fly a little underweight, always with my full water bottle and start eating empanadas for breakfast.

LEARNING TO FLY

Our instructor Russell is from Alaska. And my Colombian homegirl Juliana doesn’t speak English. So Russell teaches our physics, weather and astronomy lessons in a special, Russell branded Spanish. Diagrams and arrows and numbers crank out of the whiteboard. I crack beers and scribble down notes in both languages.

I learn how to identify clouds, how to deal with a collapse, air traffic patterns, barometric pressure and how the Coriolis Effect changes thermals.

My brain starts going fuzzy.

At 6pm, Russell will crack a beer and erase the whiteboard and I’ll exhale.

Every morning, us girls scoot two minutes up the sidewalk-less road to the fly site with our gear. At our feet, ants march by with leaves so giant you can’t see the ants, they’re just hovering chunks of color. Motorcycles fly by and honk and stare. Sometimes there’s this one dog that lays in the road, rolls around on the asphalt, and jerks to the side at the last minute which makes me shiver.

The fly site is full of pilots from Bucaramanga, foreign pilots, pilots waiting to take people on tandems, and onlookers. There’s the Master Windsock, a pilot lounge, and maybe ten picnic tables under a big metal roof. You can buy strange fruit ice cream pops, and lunch that changes every day and is always verbal. A standard lunch is meat, rice, yucca and plantains with lilikoi juice for $2.50. Shadows of paragliders drifting by darken people’s faces for a second. Kids shout and you can hear material being unpacked and flapping in the wind. I like the camaraderie up here. There’s sign prohibiting catching Pokemon Go on the premises, and a photograph of some poor idiot that landed in a eucalyptus tree last year.

The first few days I learn to control the glider on land, which is called ground handling. Without taking off. Of course a couple afternoons are uber windy, and I have to be yanked down as I’m immediately airborne. Against my wishes. Watching sweat bubble up on Russel’s face. “See why we’re not flying right now?!”

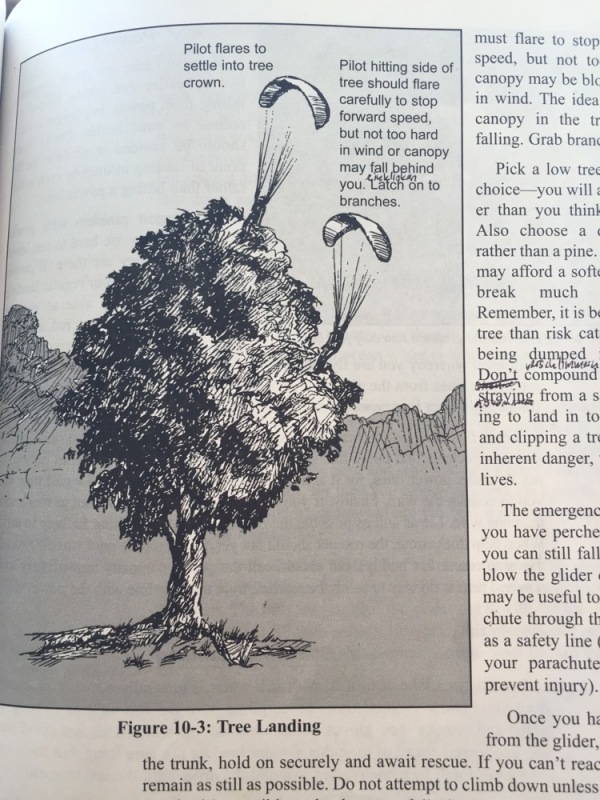

We learn about the cascading network of support lines from the risers (the ends) to the wing. A single line can hold 300 kilos, so strength is not an issue. Other things are an issue. Like power lines and tail winds, accidental spirals and tree landings.

We learn to shift our weight and how to use the brakes. Girls tend to be better at learning to paraglide, Russell says. Driving this thing requires finesse, not muscle.

But after several days of ground handling, and stubbing my brain on a textbook that would kill a mouse if dropped, there’s nothing left to do but give it a go. Alone.

A FIRST TIME FOR EVERYTHING

“Radio check Russel, do you copy?”

Crackle pop.

This is my inaugural flight. I am in fact, rather hungover. I’d gone into town the night before testing beers at different cafes, or bars I’m not sure. Then I got to experience the gas station. Young people actually pay an entrance fee to go hang out with other young people in gas station parking lots that are like outdoor clubs. Last night the fifty or so motorcycles were parked in a long line together, and people gathered on a low concrete wall drinking and laughing. A group of maybe thirty more bikes pulled in. It’s just getting started, my friend tells me. A shiny car pulled up, opened the hatch to a megasonic purple LED backlit stereo system and proceeded to blast the gas station’s tunes into oblivion while people peeled off the wall to dance.

Anyway I’m sober but lacking some coordination. I’d kick myself if I wasn’t attached to all these lines and carabiners.

“Rrrrrussel check.”

I can’t see him, but he’s driven his motorcycle to the landing site (from the air, it looks like a field among fields but with a painted wooden bullseye squashing down a ring of seedy grass) to watch me land and yell into the radio, “left! Your other left!”

I glance at the wind sock and back at instructor German’s face. I’m strapped in, poised and nervous as hell. Any minute German will yell, “Ok this is good cycle! You go!”

And he does.

I run off the grassy launch. It’s magic. I feel my glider flush with air buoying me and I’m airborne. I dangle for a minute, steering left, and then I push off my foot strap to settle into sitting position in the harness. There’s the rush of wind. The geometry of a city of million splayed in front of me and deep green mountains to my right.

I look up at my wing- I pull a little right brake and watch the right tip tug. It’s bizarre how calm I feel now, I don’t feel like I’m moving fast. I look down at the ground. I’m slowly overtaking fences, cows gathered in a knot, bushy heads of trees. I hold my toes to the horizon like Russell taught me and check to see if any landmarks disappear to the left or right into my shoes. Nope, my heading is clean, I’m going right into the wind. When I get close to the landing, I do some S-turns to lose height, taking note of the big black heads of vultures sunning themselves ontop of a nameless tree.

Whereisyourbreakpressure? Outofyourseat!

Keepyourhandsuphandsup! and finally, FLARE!

I’m on earth again. I didn’t die.

I think I could get used to this.

And so we go again.

THERMAL TIME

So it’s my third flight. Previously I have spent 4 or 5 minutes ambling down to the landing zone, but this time I hear, “uhh Marina it looks like you got a thermal 200 yards ahead. Look for the birds!”

A thermal is a rising column of hot air. It’s the prize and the glory. Thermals are invisible, so they’re challenging to find. I’ve been taught to look for the vultures that mark them. Birds don’t want to work hard either, so they find these natural elevators and cruise on up. From there, they can glide out to their next destination. That’s my goal too.

I head towards the birds and brace myself for the turbulence between rising hot air and falling cooler air. I keep pressure in my brakes, and bump into my first thermal.

“Start your 360! Feel the direction!”

I’m supposed to feel which way the wind is strongest, and turn against that feeling. I have no idea which way to go but turning left is easier, so I shift my weight left, pull my inside brake gently, and forget about my outside brake completely.

“Remember your outside brake!”

Below me I can see the black heads of the vultures banking left with me. This means I made the right choice. Cool. One vulture has long shiny black plumes and another has a wing with missing tips; beat up and scraggly feathers. I keep turning. I wobble. I play with my outside break, which helps to stabilize or speed up my turns.

After a few minutes, it dawns on my that I am truly rising.

As earthly humans, we aren’t born with air sense like birds. I have to take the picture of teeny tines trees and match it up in my brain with really fucking high.

Where I used to be able to see just the landing zone and the city, now I see the crumb of the grassy launch site. In fact I see the whole mesa that the launch site is on. I see back into the throat of the Andes where colors start to fade. Tiny blue pools sparkle in the sun. There’s some lake full of white puffy clouds. There’s long green shoulders of mountains topped in mist. And I climb.

I climb and climb in giddy circles, just me the white noise of the wind. I’m grinning.

“Follow those birds!” The radio yells.

My arms hurt from holding them up and pulling into turns but I follow those damn birds. Thermals change as you increase in altitude. They spread out. They also ooze with the wind; instead of long straight columns, they bend and dance.

My mouth starts to go dry.

I look down, way way down, and have to blink. The size of a fingernail, whirring somewhere by the city, is a helicopter.

WHO THE HELL DOES THIS KIND OF THING?

Every morning Vietnam vet and pilot Jim, who’s in his seventies, rolls through the hostel on his way go run off the mountain. Then there’s Canadians Stew and Molly. I make the mistake of asking Molly if anything has gone wrong while flying, and she recounts barely missing a barbed wire fence and plopping down in a nearby river. Here’s Molly demonstrating para-waiting for that perfect wind cycle to take off.

Molly’s dad was doing business in Colombia when he got accused of murder. Immediately, no trial, he gets locked up in prison, so Molly moved down here to help sort this out. From behind bars, he recommended they try paragliding at this world class spot in Bucaramanga.

Then there’s Stefanie, a high end fashion photographer from NYC (who claims these shoes haven’t touched anything but concrete!) and may have saved us girls from certain death several times by ordering an Uber over our cries to hitchhike again.

When she’s not making smoothies with fresh vanilla bean and practicing her German.

A pilot from Switzerland rolls through and I hear him explaining on the radio that he’s uhh, landing in a different field. (Watch out for cow pies!) Recent alum Stewart aced the course, drank all the beer, took awesome video of the girls and then disappeared to London and hopefully survived the Dengue Fever that we beat back with a homemade remedy of battered and squeezed papaya leaves.

So you wanna learn to fly in Colombia?

At Colombia Paragliding, you can stay at The Nest Hostel next door to the fly site, fly almost every day of the year, and get a ride from the landing zone back to the launch in 10 minutes to do it again.

The course is 10 days and costs $3,200,00 pesos, or about $1100. This includes instruction, gear, study materials, lodging, breakfast and laundry. Check them out at colombiaparagliding.com

Comments 3

I LOVE this–visceral insight and funny too —it made me laugh out loud:

“As earthly humans, we aren’t born with air sense like birds. I have to take the picture of teeny tines trees and match it up in my brain with really fucking high.”

You make me feel like I was there.

Nice avacados 😉

Pretty fucking rad