We have no cell phones, no Lonely Planets and no internet. But we know someone you can stay with, our friends said when we left Italy. His name is Hadley Suwell and he lives in Port Antonio. We smiled. See, I thought to myself. We got this. We don’t tell anyone and board a plane to Jamaica.

At the one story airport, the bald headed immigration officer tells us to “watch out fo dem rastas” before he stamps our passports. When we agree to a cab ride with two rastas outside the terminal, (we were mobbed, these guys were just the pushiest) they tell us to “neva trust da bald heads” and laugh. Kate and I eye each other, ducking into the car.

We peel off from the terminal and a dark hand shoves a bulging joint into the backseat. There’s more laughter. Maybe they’re stoked that they got us as passengers.

We’re here! And we’re so high! And so pale! Where are we? Where are we going? We speed around corners and the music gets louder. Another joint appears. This is when I look around the car. There’s no fare meter, no long license number or logo. There’s just the blaring radio, the steering wheel with a patch missing like a dog took a bite, and them.

“Hey what are you doing?” Kate yells.

The rastas have pulled up a driveway off the main road and now we’re idling in front a hill so thick with jungle that I can’t see any house. Just thick green leaves and vines. It smells dank and the light is dimmed under all the oozing plant life. I can’t tell if the rastas are arguing or talking but it doesn’t sound like English. Then the driver holds his hand up to his friend and looks back at us.

“No frett, no frett.“ He says, smiling with teeth and turning away.

The car doors slam shut just out of synch and Kate squeezes my thigh.

The guys stand in front of a mailbox, and one of them tilts his head up to let out a very specific whistle.

“What the fuck are they doing?” I whisper.

“I don’t know, I don’t know. Maybe–”

Something drops into the mailbox with a thud. The driver pockets it and they hop back into the car. We don’t say anything.

Buildings pop up and the heat starts booming and bouncing off metal sheds and roofs. There are suddenly people on the streets– carrying colorful bins, plastic bags, chickens, bananas. One guy sits on the curb with a single black sock on, staring. I rub the strap of my backpack and close my eyes.

So high. So high that I only catch parts of this.

“I don’t have $20 dollars!” Kate is leaning forward and yelling, one hand on the front seat.

She’s lying. I can’t tell if it’s working but I’m guessing not.

I look from the front to the back like a boxing match. My heart is speeding up and I know I should care but I’m just so thirsty.

Something about the weed we’ve been smoking. Money, more money.

Then I’m blinking in the bright sun on the side of the road and they’re screeching off. Not that we really knew where we were going anyway. I vaguely wonder how much money she gave them.

The black smoke clears and Negril comes into focus. We pick up our packs and start walking. Little shacks are jammed next to each other with sand floors that block the ocean. Jerk chicken stands puff long clouds of spicy smoke. Oil barrels are filled with trash when I peek in. We walk over a concrete bridge, sweating, and of the sun glares off colorful plastic floating on the water. There are shops and gates and diesel smoke. Itching dogs. And the heat.

Heeey darlings. Oh baby! Wanna riiiiide?

Cars slow down to our walking pace, and others fly around them. We ignore the cars. Walk straight ahead and turn corners with conviction. Sometimes waiting a minute and then turning right back around.

The first lodging we see has palm thatched rooms sprawled over a lawn off the main road. The owner, we’ll call him Tony, will make us fresh squeezed orange juice every morning and loan us bikes without brakes. He’ll give us coconuts and sugarcane and it will all seem so sweet unil the day we leave and he tries to shove his tongue in my mouth. But anyway. Feral cows dissect trash beside us. We settle in. Read books. Pass rastas on the street whose whites of their eyes have gone completely yellow. We find weed laying in the lawn and that keeps us busy for a while.

One day we’re in the car with Tony. Why, I couldn’t say. But Tony is explaining that his cousins are coming from the US, and we giggle and lean forward.

“Really! What are they like?”

“How old are they?”

Silence at the wheel.

Maybe he didn’t hear us.

“Tony,” I say louder, “what is your family like? We can’t wait to meet them!”

Tony whips around, still driving forward at full speed.

“I. Don’t. Talk. About. People.” He stares at us for a little too long and swerves back into his lane, staring straight ahead ahead.

“Only ting dat matters is now,” he announces to the windshield. “We here now. We don talk bout people because dey not here now.”

I slouch down in my seats.

Back at the cabanas, we ask the maid if maybe we can come home with her? She’s the one that sits in the sun from 9-5, rubbing fabric together in grey soapy bins. A smile sprouts on her face and starts spreading. Her head begins to nod and then gets faster. What is she thinking in that head? We make plans for the following day.

We bought a cheap tape player at the market yesterday, but I think it’s a lemon. It slows down songs like it’s low on battery but it’s plugged in. We smoke, listen to our warped player, and wait for tomorrow.

We board the bus with Jennifer after work. We get off when the bus is almost empty, far from Negril at the base of a hillside that rises up from a big green basin filled with sugarcane fields. It smells like smoke and the sun is getting low.

The settlement of Refuge climbs up the hill webbed with red mud roads between shacks. There’s a boy who brings water up the hill on his animal, and he walks with us, jerking the donkey’s rope away from the weeds as we climb. Most people aren’t wearing shoes. Jennifer grunts at some people, nods at others.

“I built this myself,” Jennifer announces, stopping half way up the hill in front of a patchwork wooden door. She twists her tiny key into a lock the size of the one on my diary when I was twelve. There’s one bed on the dirt floor. Fake flowers are tacked to the wall. She flips on a battery light declares we are going to make beer.

Jennifer steers us over muddy trails, left at this banana patch, around Johnnyboy’s shack and then someone else’s, until I’m sure I’d never find my way back. Some of the shacks glow a dim orange, some are all dark. We step into one of these black shacks and follow Jennifer to a window covered in iron bars. The only light is a single candle on a ledge that illuminates an Indian man’s face and shelves of cartons and jars and things I don’t recognize. We return to Jennifer’s house swinging plastic bags in the dark, but all I remember is grating nutmeg into a bucket and laughing. I wonder briefly where her children are sleeping. Then I’m falling asleep drunk, three of us on top of the covers. She had handed each of her four kids a plate when we first arrived, and I turned away when I saw what it was. Big reflecting eyeballs, little flecks of meat and rows and rows of white bones.

There’s no privacy here. People live in their mess, their kids, their piss, dishes, dogs and donkey shit, clean and dirty clothes and everyone else’s.

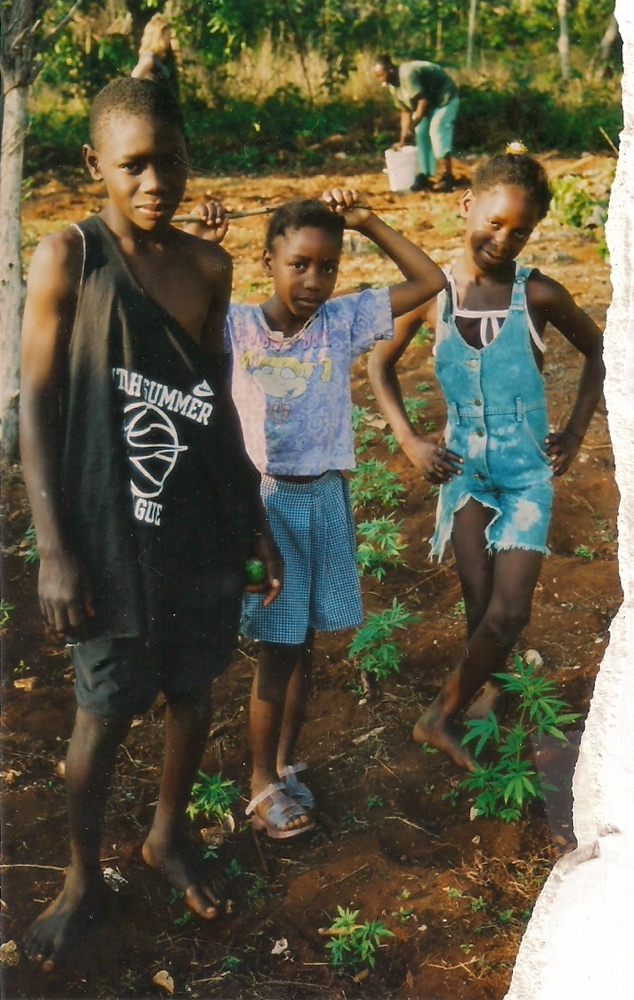

In the morning the kids want to show us something, so we climb to the top of the hill where there’s a clearing in the jungle. Little metal frames stick out of the ground, their paper plaques erased by rain. The barefoot girl scrapes leaves and gunk from one of the only stone markers with the end of a stick.

Not sure what to say, one of us asks, “what do people die from?”

“Stabbings,” one of them says.

“Diarrhea,” the other pipes up.

Somewhere near the graveyard we’re lead to the medicine patch. They giggle and touch the leaves.

One night in Refuge was enough. We’re back on the beach in Negil, planning our trip to Port Antonio. We want to find this guy Hadley. I mean, we never planned to come to this dirty tourist trap town. Then again we didn’t really plan anything.

We can see a dark woman running in our direction over the blinding white sand. In Negril there’s a beach for tourists and beach for locals. It’s unusual to see a Jamaican on this beach. There are dark storm clouds low in the sky in every direction, but the sun is shinning hot and straight down. It makes my eyes hurt.

There’s also a local guy wading through the water.

“ALOE!” He waves his hand towards the pink tourists on the beach. He’s ripped the aloe plant from the ground somewhere and he’s yelling about $100 JA. I lower my sunglasses onto my eyes. The woman is still running straight at us.

“Did you hear about the prison break in Spanish Town?” I ask Kate.

“What?” She puts her book down and frowns at me.

“17 prisoners. I mean, where could 17 people actually go on an–”

“Oh shit.” I look at Kate, and nod towards the woman. She’s slowing to a walk, her eyes locked on us.

Then she’s kneeling at my beach chair.

“Jennifer is sick,” she pants.

We stare. Who is this lady?

“She needs medicine.”

I look at her face. She says she’s Monique, Jennifer’s daughter. How many kids could Jennifer have? This would be her fifth. I can’t read Monique’s eyes. She doesn’t look side to side, just straight at our faces. I can’t tell if she’s lying or not. Was Jennifer at the cabanas today? I squint my eyes, trying to remember but there’s no time.

We fumble in our purses and hand her some money. She nods, and runs away.

The next day, Monique is back at our chairs.

“We need food,” she says. “Money.”

We are silent. I look at Kate but she just widens her eyes, giving me no clues.

I turn back to the Monique. “Let’s go to the store then,” I say.

She looks us over. Down at our purses in the sand. And she nods.

We all walk to the market, and it’s a quiet walk this time. There are no catcalls, no yells, no slowing cars. Inside the market, a boom box is blaring a scratchy Buju Banton song. I know we’re in trouble when Monique grabs one of the giant shopping carts. She takes off like she’s on a timed shopping spree, throwing boxes of cereal, chocolate cookies, cheetos, loaves of bread and crackers in the giant cart.

I yank the handle and hold up the cookies and marshmallows. Some line must be drawn. “No dessert!” I fumble. “Just food.”

She shrugs and shoots forward. By the time we’ve hit the checkout line, the cart is full and rounded at the top. If we went around a corner, cartons would tumble off. We pick out the spice buns, cheetos and fruitcake and set them on a stack of magazines. It’s still comes out to more then we’d spend on food in a week.

We hand Monique more money for a taxi and there’s no smile or thank you. We watch her struggle away with the four giant bags, not understanding. She’s trying to lift one arm under the weight to signal a car. People stream around us. Dogs itch. The sun bakes.

A older woman comes up behind Monique.

“How far you go?” She asks.

Monique shrugs.

The woman takes half of the bags and they walk together over chunks of broken sidewalk until a taxi screeches to a stop. The woman hands Monique back the bright green bags. Monique nods, shoves her things inside and both women continue on their way.

We are wandering the streets of Port Antonio after hunting down Hadley Suwell’s address. But it’s not a house, it’s a watch repair shop. I can’t recall any face, just a voice.

“No, no mon. Hadley gwon live New Jersey now.”

“What?! Oh. Well. Thanks.”

Slam.

We stand for a minute, sweating. I feel dizzy from the taxi ride. I thought we were going to kill someone, screaming through little towns while kids played soccer in the streets, running out of the way and shrieking. I kept pinching the loose cloth seat. Now we walk slow under the weight our packs. Heavy with warm clothes we brought for Europe. We come up on a restaurant with a shaded porch and fall into the hot-to-the-touch metal chairs. We put back sweating Red Stripes watch people stream by. We still have no plan. But we spot a minibus across the street that’s has Ocho Rios painted on the side, so we hop on. A man sleeps on me for most of the ride, making my neck and shoulder sweat. I didn’t know my neck could sweat. And we walk again in this bigger, rougher town. Not sure if we’re in a better position than we were a few hours ago.

We amble into a market under a patchwork of tarps, the sunlight dimmed but the heat radiating, making the smells of citrus and rot stronger. We step over trash and fruit peels, trying not to knock things over with our packs. This is where Peter just kind of appears.

He picks a rambutan from a wooden crate and hands it to us. “You try diss! Try!”

I look at Kate.

“Isn’t he going to pay for it?” I whisper when he turns back around.

The woman sitting behind the stack of crates looks away, bored. Should we pay for it? But I remember that nothing here makes sense. Peter snakes left, right, around cartons of bright fruit and stools and we follow, sucking the white flesh around the rambutan seed.

“Do you– know everybody?” Kate asks.

“Naw. Is da market, mon.” He says without looking back, and walks deeper.

Peter picks up a lilikoi, a cherimoya, and a nutmeg shell. Grabs a tomato and eats it whole. Crumples a leaf of cinnamon and shoves it into my nose.

“Peter!” Kate yells.

“Cha!”

He whips around.

“We need somewhere to stay. Like somewhere really cheap.”

He squints. “Really cheap?”

“Yeah.”

He stares for a minute. “Come.”

We’re climbing a dark concrete staircase to some high floor, maybe the fifth or sixth. It’s dark now and Peter is rolling a joint on a metal chair in the corner, smiling. He’s always smiling. Kate’s laying on the bed with her eyes wide open. I suck my sugarcane one by one out of the sticky bag and they taste so fucking good. Have we been smoking this whole time? The curtains are a kind of gray that comes off on my fingers. The one lamp is weak and yellow. There’re fleas or bedbugs or something in the bed but there’s nowhere else to be so we just keep slapping our legs and yelping. Bass from the club on the ground floor rattles the windows. We passed it on the way in–the sign said The Roof. I stared at it and my forehead hurt. I don’t understand anything here.

Kate writes something in my diary and slides it over the bed when Peter bends over to lick the joint closed. I’m scared right now, is scrawled in big blue letters over half the page. I like him but I don’t know. I got the jitters and maybe it’s time for him to go.

We have to literally push him out while he chatters on and smiles, and we sit back on the bed, breathing. But I can’t think. I just hear BOOM. BA-BA BOOM CHA, mixed with other music from outside, from other rooms and cars on the street. I can’t pick out a word from any of it. The door is still open. In an instant a woman appears in a skin-tight blue skirt, laughing and holding onto the wall for balance. Thick lipstick, blue eyeshadow. When she sees us she squeals, laughs again, and skitters away on high heels that echo down the concrete hallway.

Cheap.

Cheap.

It’s only now I get that this is a whorehouse.

The next day we take a minibus to the tiny town of Long Bay. We walk until we see a sign advertising rooms over the beach and set our packs in a little room with white lace curtains that frame the foaming waves in the dark. I get so high that Kate writes out a proclamation for me to sign. On April 4, I, Marina Galvan, did eat an entire jar of peanut butter in one sitting. I scribble an M and some loops and fall back on the bed.

Later we wander down to the beach where there’s a little restaurant with plastic chairs in the sand.

“If you ever need something from the grocery store, call this number,” the owner says and hands us a business card. He’s from California and I wonder how he ended up here.

“Oh no, we don’t need room service or anything.”

“No, not like that. This is a small town. He only comes down if there’s a customer.”

“Oh. Thanks.”

“And one more thing. Don’t go out at night, you girls,” the guy stares. “You hear me?”

“Why?”

“There’s been rapings every Tuesday through Friday. Just white girls though. And only at night.”

We’ve talked, turned the light out, on, talked more and turned it out again when I hear her voice squeak, “you wanna go home tomorrow?”

There’s no pause.

“Yeah.”